Chiropractors have a public and health care (scientific) perception as the “go to” provider for low back pain and neck pain. This was confirmed in a large recent review of the chiropractic profession. It was published in the journal Spine in December 2017, and titled (1):

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors

of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults

Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

The data for this study was from the National Health Interview Survey, which is the principal and reliable source of comprehensive health care information in the United States. The authors note that there are more than 70,000 practicing chiropractors in the United States. Chiropractors use manual therapy to treat musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. The authors state:

“The most common complaints encountered by a chiropractor are back pain and neck pain and is in line with systematic reviews identifying emerging evidence on the efficacy of chiropractic for back pain and neck pain.”

“Back pain (63.0%) and neck pain (30.2%) were the most prevalent health problems for chiropractic consultations and the majority of users reported chiropractic helping a great deal with their health problem and improving overall health or well-being.”

“Our analyses show that, among the US adult population, spinal pain and problems – specifically for back pain and neck pain – have positive associations with the use of chiropractic.”

“Chiropractic services are an important component of the healthcare profession for patients affected by musculoskeletal disorders (especially for back pain and neck pain) and/or for maintaining their overall well-being.”

In contrast to common lay perception, chiropractic adjustments (specific line-of-drive manipulations) only rarely “unpinch” pinched nerves (2). Compressive neuropathology is the rarest type of spine pain seen in chiropractic clinical practice (2).

PAIN NEUROLOGY

Pain is an electrical signal interpreted by the brain (3, 4). The electrical signal of pain is brought to the brain by nerves (5). The pain electrical signal most often begins in response to tissue inflammation (6, 7).

EMBRYOLOGY

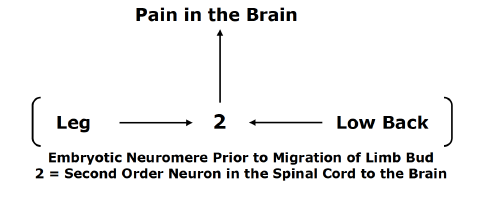

The nervous system develops in segments called neuromeres.

The low back neuromere is shared with that of the pelvis and legs.

The neck neuromere is shared with the shoulders and arms.

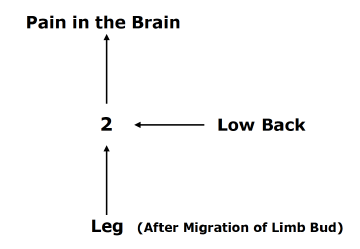

The nerves of the legs and low back arise from the same embryologic neuromere. The nerves of the legs and low back use the same second order neuron in the spinal cord to send the pain electrical signal to the brain. With the growth of the fetus, the limb bud migrates, but it maintains its embryotic neuromere.

This organization of the nervous system can confuse the brain as to the site of origin of the pain signal. The brain may perceive low back inflammation and/or irritation and hence pain as arising in the leg, and vice versa: a leg problem may be interpreted as arising from the low back. This phenomenon is called referred pain. Identifying and treating the actual site of the pain signal is quite important in achieving a good clinical outcome.

The same referred pain phenomenon exists between the arms and neck, as well as in other parts of the body.

Spinal Cord

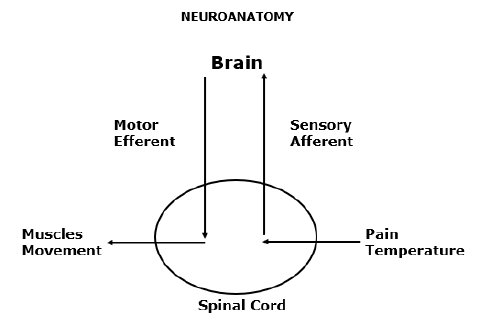

A simple but accurate way to categorize the nervous system is into two separate but integrated systems (above):

1) The MOTOR nerve system:

- The motor nerve system is shown on the left side of the drawing.

- The motor nerve system begins in the brain, travels down the spinal cord, exits the spinal column, and innervates the muscles.

- The motor nerves are also called efferent nerves because they originate in the central nervous system, leave the spinal column, and innervate muscles.

- The motor nerve system controls movement and strength.

2) The SENSORY nerve system:

- The sensory nerve system is shown on the right side of the drawing.

- The sensory nerve system brings electrical signals from the peripheral body into the spinal cord, up the spinal cord, and into the brain.

- The sensory nerves are also called afferent nerves because they originate in the peripheral body, travel to the spinal column, and terminate in the brain where the electrical signal is perceived and interpreted.

- Pain and temperature are sensory nerve signals (there are others).

Category 1 Patients

Inflammatory Pain

In 1976, spine care pioneer Alf Nachemson, MD, noted that only tissues that have a sensory nerve supply are capable of sending the pain signal to the brain (8). Almost all tissues of the spinal column have a sensory nerve supply and are therefore capable of initiating pain perception. In 1991, Stephen Kuslich, MD, and colleagues, using invasive irritations on 700 conscious subjects, documented the spinal tissues that are capable of initiating low back pain. These include (9):

- Skin

- Superficial Muscles

- Deep Muscles

- Intervertebral Disc

- Facet Joint Capsules

- Periosteum of the Vertebral Bone

- Nerve roots

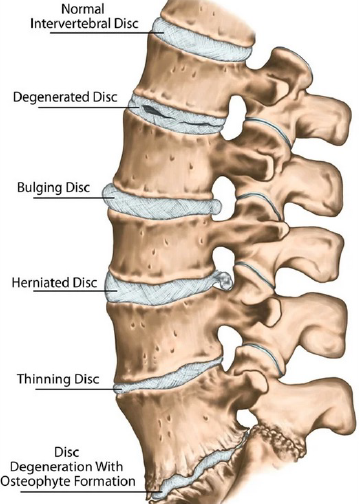

Chronic low back pain was primarily attributed to the intervertebral disc (9). The perspective that chronic low back pain is primarily discogenic is supported by others (10, 11, 12).

In the neck, similar to the low back, the same tissues are capable of initiating pain. In contrast to the low back, persistent neck pain is primarily attributed to the facet joint capsules (13, 14).

Successful management of Category 1 Patients (Inflammatory Pain) involves a variety of anti-inflammatory interventions. Some, such as the commonly used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are helpful but are associated with horrible and unacceptable side effects (15, 16). Ice is often helpful.

Chiropractic care is proven to be very successful in the treatment of chronic low back and neck pain. Often, chiropractic care is superior to alternative types of management for both, including prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, exercise, and needle acupuncture (2, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). Undoubtedly, this is the basis for clinical guidelines to routinely advocate chiropractic care and spinal manipulation for the treatment of spinal pain (24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29).

The benefits of spinal adjusting in these patients are attributed primarily to two mechanisms:

A) Mechanical dispersion of inflammatory chemicals (10):

Spinal adjusting improves spinal motion, and improved spinal motion disperses the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals. This is especially true with respect to discogenic pain, as the intervertebral disc is avascular. Only improved motion can disperse the nociceptive chemicals.

When Vert Mooney, MD, was the president of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, his Presidential Address emphasized this concept, stating (10):

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“The fluid content of the disk can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration [in the disc].”

“Research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually, the human intervertebral disk lives because of movement.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disk. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

B) Closure of the pain gate (2, 30, 31):

The pain electrical signal can be “blocked” by closing the “pain gate.” Spinal adjusting can initiate a mechanical electrical signal that does this. This concept was first proposed by pain researchers Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall in 1965 (30). Their theory is known as the Gate Control Theory of Pain.

In 2002, the British Journal of Anaesthesia published a study reaffirming the validity of the Gate Theory of Pain in an article titled (31):

Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time

Theoretically, spinal stiffness would allow the pain gate to be open to nociceptive electrical signals; spinal adjusting would improve mechanical motion and close the pain gate to nociceptive signals. This explanation was first advanced by Canadian orthopedic surgeon Kirkaldy-Willis in 1985. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis stated (2):

Melzack and Wall proposed the Gate Theory of Pain in 1965, and this theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.”

“The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

The facet capsules are densely populated with mechanoreceptors. “Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Other publications have supported this model (32, 33).

Category 2 Patients

Sclerogenic Referral Pain

Many patients who suffer with low back pain also have pain in their leg(s). Many patients with neck pain will also have pain in their arm(s). Although such a clinical presentation leads to concerns of spinal nerve compression (Category 3 Patients), it is usually something else. It is referred pain, as described above in the section on EMBRYOLOGY. Technically, it is also known as Sclerogenic pain, Sclerotomic pain, or Sclerotogenous pain.

Sclerogenic leg pain occurs as a consequence of an irritation of spinal tissues below the deep fascia (deep spinal muscles, spinal ligaments, intervertebral disc, etc.). It does not involve irritation, inflammation or compression of the spinal nerve roots.

The existence and patterns of sclerogenic pain has been documented for nearly a century (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42).

Sclerogenic pain often subjectively presents as a deep, diffuse dull ache that is not in a dermatomal pattern. It is difficult for the patient to precisely locate the pain on the skin; the discomfort is perceived deep to the skin.

Typically, sclerogenic pain presents with these examination findings:

- Spinal compression tests (Spurling’s, Kemp’s, etc.) are usually negative.

- Valsalva is usually negative.

- Straight leg raising and the brachial plexus tension tests are usually negative.

- Myotomal strength tests are usually normal.

- Deep tendon reflexes are usually normal and symmetrical. In general, sclerogenic pain is not complicated or dangerous. Chiropractic spinal adjustments primarily affect the deep spinal tissues that are responsible for the sclerogenic pain referral. Consequently, chiropractic spinal adjusting is very effective in improving and/or resolving both back pain and referred sclerogenic leg pain.

Category 3 Patients

Nerve Root Involvement

Irritation, Inflammation, Compression

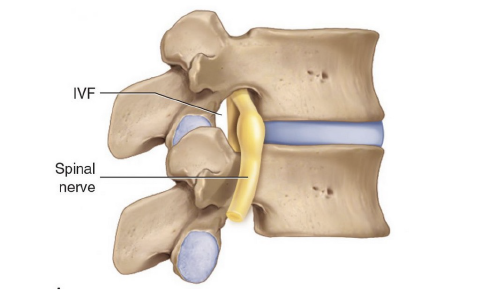

Between every spinal segmental level there is a spinal nerve (nerve root). This arrangement exists in all spinal regions: neck, mid back, and low back. Spinal pathology has the potential to irritate, inflame, and/or compress the nerve root. The technical term for these nerve root problems is radiculopathy.

In the neck, the spinal nerve root extends down the shoulder and into the arm(s). In the low back, the spinal root extends down the pelvis and into the leg(s). Consequently, when a nerve is irritated, inflamed, or compressed, it generates symptoms (pain, numbness, tingling, hypersensitivity, burning, achiness, etc.) and/or functional disturbances (weakness, atrophy, etc.) in the arm(s) and/or leg(s).

The most common cause of nerve root irritation, inflammation, or compression is herniation of the intervertebral disc. Other causes include arthritic changes (degenerative joint disease, degenerative disc disease, spondylosis) causing narrowing of the intervertebral foramen.

Radiculopathy is more complex and concerning than local pain or sclerogenic pain syndromes. As a rule, nerve root irritation and inflammation resolve with chiropractic spinal adjusting. However, they often require longer treatment duration and more frequent chiropractic visits. To rule out serious pathology that may be causing the irritation and/or inflammation, chiropractors may use diagnostic imaging, primarily x-rays. On occasion, the chiropractor may determine that advanced diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT, etc.) is warranted.

Compressive radiculopathy is the most concerning clinical syndrome seen in chiropractic clinical practice. This is because excessive or prolonged compression may lead to death of some of the nerve fibers resulting in permanent functional impairments.

Typical clinical findings in patients with compressive radiculopathy include:

- Positive spinal compression tests (Spurling’s (neck), Kemp’s (low back), etc.).

- Positive Valsalva test.

- Positive straight leg raising (low back) and/or the brachial plexus tension (neck) tests.

- Myotomal (muscle) weakness.

- Reduced deep tendon reflexes.

- Altered superficial sensation in a dermatomal pattern.

Red flag findings that warrant referral for additional investigations include:

- Muscle group atrophy.

- Loss of normal function of bladder, bowels, or sexual function (difficulty starting, difficulty ending, dripping, loss of sensation, etc.).

- Saddle anesthesia (loss of sensation in the area of the buttocks that would contact a saddle when sitting).

- Loss of bowel, bladder, and/or sexual function.

In addition to diagnostic imaging (x-rays, MRI, and/or CT scans), compressive radiculopathy may warrant the use of neuro-diagnostic testing (electromyography, nerve conduction studies, etc.).

Statistically, compressive neuropathology is very rare, constituting only 1-2% of chiropractic clinical practice. For seven decades, studies have shown that spinal adjusting is appropriate and usually successful in the management of compressive radiculopathy (43, 44, 45 46, 47 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55).

Rarely, patients suffering from compressive radiculopathy will require a surgical decompression. Chiropractors are trained to monitor patient progress for any symptoms or signs that might benefit or require a surgical consultation.

SUMMARY

Chiropractors primarily treat and manage spinal pain syndromes. Ninety-three percent of initial chiropractic care is for the management of low back and/or neck pain complaints (1). On these patients, a number of mechanisms may be responsible for improvement in the patients’ signs and symptoms. The explanations most commonly used are (A) the dispersion of inflammatory chemicals and (B) the initiation of a neurological sequence of events that closes the pain gate.

When a patient presents with spine pain and extremity (arm or leg), complaints (pain, tingling, numbness, etc.) clinical thinking changes. Initially, the chiropractor will determine if the extremity complaint is sclerogenic referred or if it is compressive radiculopathy. In the case of sclerogenic referral, successful management of the deep spinal tissue irritations will resolve the extremity symptomatology, and this is effectively accomplished with spinal adjusting. Typically, the spine complaints and the extremity symptoms will resolve together.

In the case of suspected compressive radiculopathy, chiropractors will do a more detailed evaluation, which may include imaging and/or neuro-diagnostics. The chiropractor may decide to treat the condition, refer the patient to another provider, or co-treat the patient with another provider.

REFERENCES

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T; Principles of Neural Science; McGraw-Hill; 2000.

- Ambron R; The Brain and Pain: Breakthroughs in Neuroscience; Columbia University Press; 2022.

- Gunn CC; The Gunn Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain: Intramuscular Stimulation for Myofascial Pain of Radiculopathic Origin; Churchill Livingston; 1996.

- Boswell M, Cole BE, Editors; Weiner’s Pain Management: A Practical Guide for Clinicians; American Academy of Pain Management; Seventh Edition; 2006.

- Omoigui S; The Biochemical Origin of Pain: The Origin of All Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response: Inflammatory Profile of Pain Syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; pp. 1169 – 1178.

- Nachemson A; The Lumbar Spine, An Orthopedic Challenge; Spine; March 1976; Vol. 1; No 1; pp. 59-71.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; April 1991; Vol. 22; No. 2; pp. 181-187.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, D’Aprile P, Muto M; Spine Pain; European Journal of Radiology; May 2015; Vol. 84; pp. 746–756.

- Bogduk N; Functional Anatomy of the Spine; Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Vol. 136; pp. 675-688.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C; On the Nature of Neck Pain, Discography and Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Blocks; Pain; August 1993; Vol. 54; No. 2; pp. 213-217.

- Bogduk N; On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash; Spine; December 1, 2011; Vol. 36; No. 25S; pp. S194–S199.

- Giles LGF; Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty Acids (Fish Oil) as an Anti-Inflammatory: An Alternative to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for Discogenic Pain; Surgical Neurology; April 2006; Vol. 65; 326– 331.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; June 2, 1990; Vol. 300; pp. 1431-1437.

- The Lancet; Chiropractors and Low Back Pain; July 28, 1990, p. 220.

- Muller R, Giles LGF; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Cifuentes M, Willetts J, Wasiak R; Health Maintenance Care in Work-Related Low Back Pain and Its Association with Disability Recurrence; Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; April 14, 2011; Vol. 53; No. 4; pp. 396-404.

- Senna MK, Machaly SA; Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Result in Better Long-Term Outcome? Randomized Trial; Spine; August 15, 2011; Vol. 36; No. 18; pp. 1427–1437.

- Woodward MN, Cook JCH, Gargan MF, Bannister GC; Chiropractic Treatment of Chronic ‘Whiplash’ Injuries; November 1996; Injury; Vol. 27; No. 9; pp. 643-645.

- Khan S, Cook J, Gargan M, Bannister G; A symptomatic classification of Whiplash Injury and the Implications for Treatment; The Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine; 1999; Vol. 21; No. 1; pp. 22-25.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekell, Owens DK; Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; Vol. 147; No. 7; October 2007; pp. 478-491.

- Chou R, Huffman LH; Non-pharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; October 2007; Vol. 147; No. 7; pp. 492-504.

- Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, DC, Whalen WM, Walters S, Kaeser M, Dehen M, DC, Augat T; Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2016; Vol. 39; No. 1; pp. 1-22.

- Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Goldgrub R, Nordin M, Gross DP, Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Stern PJ, Ameis A, Southerst D, Mior S, Stupar M, Varatharajan T, Taylor-Vaisey A; Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration; European Journal of Pain; Vol. 21; No. 2; February 2017; pp. 201-216.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians; For the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Annals of Internal Medicine; April 4, 2017; Vol. 166; No. 7; pp. 514-530.

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al.; Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care: An Updated Overview; European Spine Journal; November 2018; Vol. 27; No. 11; pp. 2791-2803.

- Melzack R, Wall P; Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory; Science; November 19, 1965; Vol. 150; No. 3699; pp. 971-979.

- Dickenson AH; Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time; British Journal of Anaesthesia; June 2002; Vol. 88; No. 6; pp. 755-757.

- Vicenzino B, Collins D, Wright A; The Initial Effects of a Cervical Spine Manipulative Physiotherapy Treatment on the Pain and Dysfunction of Lateral Epicondylalgia; Pain; November 1996; Vol. 68; No. 1; pp. 69-74.

- Savva C, Giakas G, Efstathiou M; The Role of the Descending Inhibitory Pain Mechanism in Musculoskeletal Pain Following High-Velocity, Low Amplitude Thrust Manipulation: A Review of the Literature; Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation; 2014; Vol. 27; No. 4; pp. 377–382.

- Kellgren JH; A Preliminary Account of Referred Pain Arising from Muscle; The British Medical Journal; February 12, 1938; pp. 325-327.

- Kellgren JH; On the distribution of pain arising from deep somatic structures with charts of segmental pain areas; Clinical Science; 1939; Vol. 4; pp. 35-46.

- Inman VT, Saunders JB; Anatomicophysiological Aspects of Injuries to the Intervertebral Disc; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; April 1947; Vol. 29; No. 2; pp. 461–468.

- Sinclair DC, Feindel WH, Weddell G, Falconer MA; The Intervertebral Ligaments as a source of Segmental Pain; The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, British; August 1, 1948; Vol. 30-B; No. 3; pp. 515-521

- Feinstein B, Langion JNK, Jameson RM, Schiller F; Experiments on Pain Referred from Deep Somatic Tissues; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American; October 1954; Vol. 36-A; No. 5; pp. 981-997.

- Hockaday JM, Whitty CW; Patterns of Referred Pain in the Normal Subject; Brain; September 1967; Vol. 90; No. 3; pp. 481-496.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual; New York; Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

- Travell J, Simons D; Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: THE LOWER EXTREMITIES; New York; Williams & Wilkins; 1992.

- Simons D, Travell J; Travell & Simons’, Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual: Volume 1, Upper Half of Body; Baltimore; Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- Ramsey RH; Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; Instructional Course Lectures; Vol. 11; 1954; pp. 118-120.

- Mathews JA, Yates DAH; Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation; British Medical Journal; September 20, 1969; No. 3; pp. 696-697.

- Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; September 1969; Vol. 15; No. 3; pp. 104-110.

- Turek S; Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications; JB Lippincott Company; 1977; page 1335.

- Kuo PP, Loh ZC; Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research; February 1987; No. 215; pp. 47-55.

- Quon JA, Cassidy JD, O’Connor SM, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation: treatment by rotational manipulation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; June 1989; Vol. 12; No. 3; pp. 220-227.

- Cassidy JD, Thiel HW, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Side posture manipulation for lumbar intervertebral disk herniation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 1993; Vol. 16; No. 2; pp. 96-103.

- Stern PJ, Côté P, Cassidy JD; A series of consecutive cases of low back pain with radiating leg pain treated by chiropractors; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; Jul-Aug 1995; Vol. 18; No. 6; pp. 335-342.

- Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S; Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: A randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations; The Spine Journal; March-April 2006; Vol. 6; No. 2; pp. 131–137.

- McMorland G, Suter E, Casha S, du Plessis SJ, Hurlbert RJ; Manipulation or Microdiskectomy for Sciatica? A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; October 2010; Vol. 33; No. 8; pp. 576-584.

- Bronfort G, Hondras M, Schulz CA, Evans RL, Long CR, Grimm R; Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise with Advice for Subacute and Chronic Back-Related Leg Pain: A Trial With Adaptive Allocation; Annals of Internal Medicine; September 16, 2014; Vol. 161; No. 6; pp. 381-391.

- Leemann S, Peterson CK, Schmid C, Anklin B, Humphreys BK; Outcomes of Acute and Chronic Patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Lumbar Disc Herniations Receiving High-Velocity, Low Amplitude, Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study with One-Year Follow-Up; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March/April 2014; Vol. 37; No. 3; pp. 155-163.

- Fritz JM, Lane E, McFadden M, Brennan G, Magel JS, Thackeray A, Minick K, Meier W, Greene T; Physical Therapy Referral from Primary Care for Acute Back Pain with Sciatica: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Annals of Internal Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 174; No. 1; pp. 8-17.

- Ghasabmahaleh SH, Rezasoltani Z, Dadarkhah A, Hamidipanah S, Mofrad RK, Sharif Najafi S; Spinal Manipulation for Subacute and Chronic Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial; The American Journal of Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 134; No. 1; pp. 135−141.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”